Legends of the Masters of the Tantric Path

The Mahasiddhas were enlightened beings who achieved spiritual perfection in a single lifetime. They were masters of the Tantric path who emphasized the use of symbolism, ritual, and meditation to attain enlightenment. Also known as the "Great Accomplished Ones," they were a group of great adepts who flourished in India between the 8th and 12th centuries. They are revered as extraordinary figures in Buddhism due to their deep spiritual accomplishments and high level of spiritual mastery over esoteric tantric practices.

These masters attained profound realization through unconventional methods, often blending meditation, rituals, and yogic practices with everyday life. Rather than adhering strictly to monastic codes, many of them lived as householders or wandering ascetics. Their lives reflected a radical freedom and insight, grounded in their direct experience of reality, which enabled them to perform what appeared as miraculous acts. Mahasiddhas became such divine beings through their rigorous dedication to tantric paths, where they combined wisdom (prajna) with method (upaya), often under the guidance of a qualified teacher.

Their transformation into a siddha typically involved the integration transcendence of both spiritual and worldly experiences. Their mastery over their siddhi is also through their devotion to a qualified guru and eventually proficiency of tantric methods. Unlike the conventional practice of relying on monastic discipline or gradual cultivation, the siddhas embraced the transformative potential of tantric techniques to overcome mental obscurations and purify karma in a single lifetime. Their exercise focused on realizing the innate purity of mind and directly experiencing the ultimate truth, often through radical and experiential approaches.

The Path to Siddhi: A Journey Beyond Spiritualism

The great adepts endured intensive inner work, visualization, mantra recitation, and deep meditation before becoming the most outstanding mystical siddhas. They purified their karma and realized siddhi, the true nature of the mind, and became liberated while still in their human form. Their teachings were then passed down to disciples which later formed the foundation of the Vajrayana tradition. Hence, their accomplishments and teachings formed the backbone of the Vajrayana tradition.

Siddhi in Sanskrit refers to the attainment of supernatural or extraordinary powers or abilities. It's a concept often associated with the following practices that the siddhas followed:

- Devotion to a Guru: Mahasiddhas often followed the guidance of a realized master, receiving direct teachings and initiations essential for progressing on the tantric path.

- Tantric Practices: They engaged in advanced practices such as mantra recitation, deity visualizations, and specific yogic techniques that aimed to accelerate spiritual transformation.

- Integration of Wisdom and Method: By combining wisdom (prajna), the understanding of emptiness, with skillful means (upaya), they cultivated both insight and compassionate action in their practice.

- Non-Ordinary Lifestyles: Many Mahasiddhas lived outside traditional monastic norms, incorporating their spiritual realizations into unconventional lifestyles as householders, wanderers, or ascetics.

- Purification of Karma: Through dedicated practice, they purified their past karma, allowing them to transcend ordinary suffering and achieve extraordinary spiritual power (siddhis).

- Attainment of Realization: Their path focused on realizing the nature of the mind, reaching states of enlightenment that allowed them to guide others while still in human form.

The Outstanding 84 Mahasiddhas

The masters are called Mahasiddhas because they attained the ultimate levels of spiritual realization (mahamudra) and possessed siddhi, the impeccable supernatural powers.

Below is the list of the 84 Mahasiddhas and their epithets:

-

Luipa (Nya'i rgyud ma za ba) – The Fish-Gut Eater

-

Līlapa (Sgeg pa) – The Royal Hedonist

-

Virūpa (Bi ru pa) – The Ḍākinī-Master

-

Ḍombipa (Dom bhi pa) – The Tiger-Rider

-

Śavaripa (Dgra bo ri pa) – The Hunter

-

Saraha (Sa ra ha) – The Great Brahmin

-

Kaṅkālipa (Kang ka li pa) – The Lovelorn Widower

-

Mīnapa (Nya ba pa) – The Fish-Rider

-

Gorakṣanātha (Go ra kha na tha) – The Cowherd Yogi

-

Caurangipa (Tsau rang gi pa) – The Dismembered Yogi

-

Vīṇāpa (Bi na pa) – The Musician

-

Śāntipa (Zhi ba pa) – The Peaceful Scholar

-

Tantipa (Thag pa pa) – The Weaver

-

Cāmāripa (Tsa ma ri pa) – The Cobbler

-

Khaḍgapa (Ral gri pa) – The Sword Master

-

Nāgārjuna (Klu sgrub) – The Philosopher

-

Kṛṣṇācārya (Kāṇha) (Nag po pa) – The Dark Siddha

-

Āryadeva ('Phags pa lha) – The One-Eyed Adept

-

Thaganapa (Rtag tu rdzun smra ba) – The Liar

-

Nāropa (Na ro pa) – The Tireless Seeker

-

Śyalipa (Spyang ki pa) – The Jackal Yogi

-

Tilopa (Ti lo pa) – The Sesame Seed Grinder

-

Catrapa (Tsa tra pa) – The Lucky Beggar

-

Bhadrapa (Bzang po pa) – The Noble Brahmin

-

Dukhaṅḍhi (Gnyis gcig tu byed pa) – The Scavenger

-

Ajogipa (A yo gi pa) – The Rejected Yogi

-

Kālapa (Ka la pa) – The Madman

-

Dhobipa (Dho bi pa) – The Washerman

-

Kaṅkaṇapa (Kang ka na pa) – The Siddha King

-

Kambalapāda (Kambha la pa) – The Blanket-Clad

-

Ḍeṅgipa (Ding gi pa) – The Courtesan’s Monk

-

Bhaṇḍepa (Nor la 'dzin pa) – The Jealous Celestial

-

Tāntipa (Taṅkripa) (Cho lo pa) – The Gambler

-

Kukkuripa (Ku ku ri pa) – The Dog-Lover

-

Kucipa (Ltag ba can) – The Hunchbacked Yogi

-

Dharmapa (Thos pa'i shes rab) – The Scholarly Monk

-

Mahipa (Ngar rgyal can) – The Great King

-

Acintapa (Bsam mi khyab pa) – The Greedy Hermit

-

Babhaha (Chas lhas 'o mo len) – The Passionate Lover

-

Nalinapa (Pad ma'i rtsa ba) – The Lotus-Born Prince

-

Śāntideva (Zhi ba lha) – The Idle Monk

-

Indrabhūti (In dra bu ti) – The Tantric King

-

Mekopa (Me ko pa) – The Dreadful-Eyed

-

Koṭālipa (Kang ka na pa) – The Peasant Sage

-

Kamparipa (Kam pa ri pa) – The Blacksmith

-

Jālandharipa (Tsa la 'dra ba) – The Ḍākinī's Lover

-

Rāhula (Ra hu la) – The Rejuvenated

-

Garbharipa (Gharbari) (Nang snying pa) – The Householder

-

Dhokaripa (Rdzong kha ba) – The Bowl-Bearer

-

Medhinipa (Sa chen pa) – The Farmer

-

Pankajapa (Pad ma 'byung gnas) – The Lotus Practitioner

-

Ghaṇṭāpa (Dril bu pa) – The Celibate Bell-Ringer

-

Jogipa (Rnal 'byor pa) – The Wandering Ascetic

-

Celukapa (Tshes lus ka ba) – The Awakened Layman

-

Godhuripa (Bya rkun pa) – The Bird-Catcher

-

Lucikapa (Gzhan 'grel ba) – The Escapist

-

Nirguṇapa (Yon tan med pa) – The "Ignorant" Sage

-

Jayānanda (Rgyal ba dga' ba) – The Blissful Victor

-

Pacaripa (Bal po sha mo smra ba) – The Pastry Cook

-

Campaka (Me tog can) – The Flower Gardener

-

Bhikṣanapa (Sprang po pa) – The Toothless Mendicant

-

Dhilipa (Tshong dpon len pa) – The Lazy Merchant

-

Dīpaṅkara (Mar me mdzad) – The Lamp Bearer

-

Nandapa (Dga' ba pa) – The Joyful Devotee

-

Vinapa (Dbyangs can) – The Tantric Musician

-

Mātāṅgipa (Mi rigs pa) – The Outcaste Sage

-

Bhūtipa (Byung ba pa) – The Alchemist

-

Lalitavajra (Rdo rje gzi brjid) – The Elegant Vajra

-

Maitrīpa (Byams pa pa) – The Lord of Compassion

-

Udhilipa (Chang 'tshong ba) – The Wine Maker

-

Subāhuka (Lag bzang pa) – The Armored One

-

Utpala (Ut pa la pa) – The Blue Lotus

-

Sukhāpa (Bde ba pa) – The Blissful One

-

Mekhalā (Me khol la) – The Headless Yogini

-

Kanakhalā (Ka na kha la) – The Headless Yogini

-

Padmavajra (Padma rdo rje) – The Lotus Vajra Holder

-

Chinnamastā (U thog gchog med ma) – The Self-Decapitator

-

Lakṣmīṅkarā (Dpal mo lha mo) – The Royal Yogini

-

Vīravajra (Dpa' bo rdo rje) – The Heroic Vajra

-

Tilaripa (Til mar pa) – The Oil Presser

-

Guhyaka (Sbas pa ba) – The Hidden One

-

Syalipa (Spyang ki pa) – The Animal-Tamer

-

Bhangura (Zal gyis 'joms pa) – The Destroyer of Illusion

-

Guhyapati (Sbas pa'i bdag po) – The Lord of Secrets

These 84 "greatly perfected beings" truly represents a pinnacle of spiritual attainment within the tantric traditions of Buddhism. They all hold a special place of reverence and intrigue. Thus, they are celebrated not only for their profound spiritual realizations but also for their diverse backgrounds and unconventional paths to enlightenment.

Mahasiddhas Shaped the Vajrayana Buddhism

As the 84 Mahasiddhas were a group of highly accomplished tantric masters, their role in shaping Vajrayana Buddhism is crystal clear. Living between the 8th and 12th centuries, primarily in India, they gained Siddhi while still in human form. What distinguishes the Mahasiddhas is their unconventional approach to spirituality. Many of them came from diverse social backgrounds, including kings, beggars, craftsmen, and even outcasts, showing that the path to enlightenment was not confined to monastic or scholarly life.

Amidst the 84 Mahasiddhas who dwell into the spiritual prowess, certain figures have become particularly renowned. Tilopa, for instance, was a fisherman who received direct teachings from celestial dakinis, culminating in his mastery of the tantric path. He then transmitted his teachings to his disciple Naropa, a former scholar and monk from Nalanda University. Naropa’s rigorous training under Tilopa’s guidance eventually led to his own enlightenment, after enduring twelve severe trials to overcome ego and attachment. His teachings were later passed on to Marpa Lotsawa, who became one of the most important Tibetan translators and the guru of Milarepa, one of Tibet's most beloved yogis.

Another notable Mahasiddha is Virupa, who began as a monk at the famed Nalanda Monastery but later embraced the tantric path. He was known for his miraculous powers, including stopping the flow of the Ganges River and holding the sun in the sky. His life is a vivid example of how the Mahasiddhas balanced spiritual realization with what seemed like magical abilities, yet they always emphasized that these powers were secondary to the ultimate realization of the mind's true nature. Shantipa, a prince turned yogi, and Kukkuripa, who attained enlightenment with the help of his loyal dog, also stand out for their unique life stories that blend the mystical and the mundane.

The teachings and lives of these Mahasiddhas provided a foundation for the Vajrayana tradition, emphasizing that enlightenment is accessible through dedication, practice, and the guidance of an accomplished teacher. Their stories continue to inspire practitioners, offering a reminder that the path to spiritual awakening is open to everyone, regardless of social status or background.

The influence and contribution of the Mahasiddhas towards Vajrayana Buddhism are profound and lasting. These masters introduced and propagated teachings that diverged from the more conventional monastic and scholastic approaches dominant in earlier forms of Buddhism. Their unique methods focused on the direct realization of the nature of mind, using skillful means (upaya) such as meditation, mantra recitation, and deity visualization to swiftly attain enlightenment. This emphasis on tantric techniques, particularly those aimed at transforming ordinary desires and emotions into pathways for spiritual awakening, became the hallmark of Vajrayana practice, which later spread to Tibet, Nepal, and other regions.

Six Yogas of Naropa

Tilopa and Naropa played critical roles in formalizing and transmitting tantric practices. Tilopa was the pioneer of the six yogas and he had devised a set of powerful meditation techniques that were passed down to Naropa. The latter then compiled the lessons as the "Six Yogas of Naropa."

These practices are a set of advanced yogic practices designed to accelerate the path to enlightenment are:

Tummo: Generating inner heat to purify the body.

Dream Yoga: Developing conscious awareness while dreaming.

Clear Light Yoga: Experiencing the luminous nature of consciousness.

Illusion Yoga: Overcoming the illusion of a separate self.

Cemetery Charnel Ground Yoga: Confronting fear and impermanence.

Yoga of Bardo: Navigating the intermediate states between death and rebirth.

These practices were then brought to Tibet by Marpa Lotsawa, who translated numerous tantric texts and established a lineage that culminated in Milarepa, whose life story exemplifies the Mahasiddha ideal of a practitioner achieving enlightenment through intense practice and devotion. This lineage, known as the Kagyu school, remains one of the most prominent sects in Tibetan Buddhism today.

Contributions of Some Selected Mahasiddhas

Then comes the Virupa, who made significant contributions to the development of the Hevajra Tantra, a central text in Vajrayana Buddhism. His mastery over tantric rituals and his unconventional behavior—such as holding the sun in the sky until he was given beer—demonstrated his realization of the non-dual nature of reality. This breaking of traditional norms highlighted the Mahasiddhas' message that enlightenment is not confined to rigid doctrines but can be attained through direct experience of the mind's true nature. Virupa's teachings also deeply influenced the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, which regards him as one of its founding figures.

The Mahasiddhas also popularized the notion that enlightenment is accessible to everyone, regardless of social standing or occupation. For example, Kukkuripa, was a beggar who lived with his dog, yet he attained realization through profound love and devotion. His story illustrates the Mahasiddhas’ rejection of the rigid class structures and hierarchical systems that dominated medieval Indian society. This democratization of spiritual practice was revolutionary and had a lasting impact on the development of Vajrayana, which encourages practitioners from all walks of life to pursue the path of awakening.

Moreover, the Mahasiddhas’ teachings emphasized the integration of wisdom (prajna) and compassion, urging practitioners to engage fully with the world rather than retreating into isolated contemplation. This active engagement with reality, combined with their focus on transforming negative emotions into wisdom, shaped the ethical and philosophical foundations of Vajrayana Buddhism. Their radical and experiential approach also led to the proliferation of various tantric rituals, art forms, and meditation practices that continue to define the tradition.

Meanwhile, here is a table highlighting some notable Mahasiddhas and their significant literary works, which have been published or compiled over time:

|

Mahasiddha |

Notable Works |

Description |

|

Tilopa |

Tilopa's Six Doctrines |

A compilation of teachings on the six yogas, including techniques for direct realization of the nature of mind. |

|

Naropa |

The Twelve Themes of Naropa |

Contains teachings on the twelve major trials (nyungne) Naropa underwent, outlining his transformative experiences. |

|

Marpa Lotsawa |

Marpa's Collected Works |

Includes translations and commentaries on Tibetan texts and teachings, particularly from the Indian tradition. |

|

Milarepa |

The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa |

A collection of songs and poetry detailing Milarepa’s spiritual experiences, teachings, and miraculous deeds. |

|

Gampopa |

The Jewel Ornament of Liberation |

A comprehensive treatise on the path to enlightenment, combining both sutra and tantra teachings. |

|

Virupa |

The Vairochana Tantra |

Texts attributed to Virupa that elaborate on the Vairochana teachings, focusing on tantric rituals and practices. |

|

Kukkuripa |

The Dog's Path to Enlightenment |

Includes teachings and stories about Kukkuripa’s unconventional practices and realizations. |

|

Shantipa |

The Method of the Wise |

A collection of teachings and commentaries attributed to Shantipa, focusing on meditation techniques and wisdom. |

|

Pema Lingpa |

The Revelation of the Heart |

Includes texts and terma (hidden treasures) revealed by Pema Lingpa, focusing on practices and teachings. |

|

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu |

The Three Lamps |

A collection of teachings and commentaries by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, focusing on Dzogchen practice and theory. |

|

Lama Tsongkhapa |

The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo) |

A seminal work on the gradual path to enlightenment, integrating both sutric and tantric teachings. |

Through the centuries, the Mahasiddhas' teachings were preserved and expanded upon by subsequent generations of practitioners. They laid the foundation for the spread of tantric Buddhism to Tibet, where their methods were systematized and adapted into Tibetan culture. Their influence extends beyond Vajrayana, particularly in the ways they emphasized the possibility of attaining Buddhahood in a single lifetime. Today, the lives and teachings of these eighty-four Mahasiddhas continue to inspire Buddhist practitioners, symbolizing the transformative power of tantra and the potential for every individual to achieve enlightenment through dedication, practice, and the guidance of a qualified teacher.

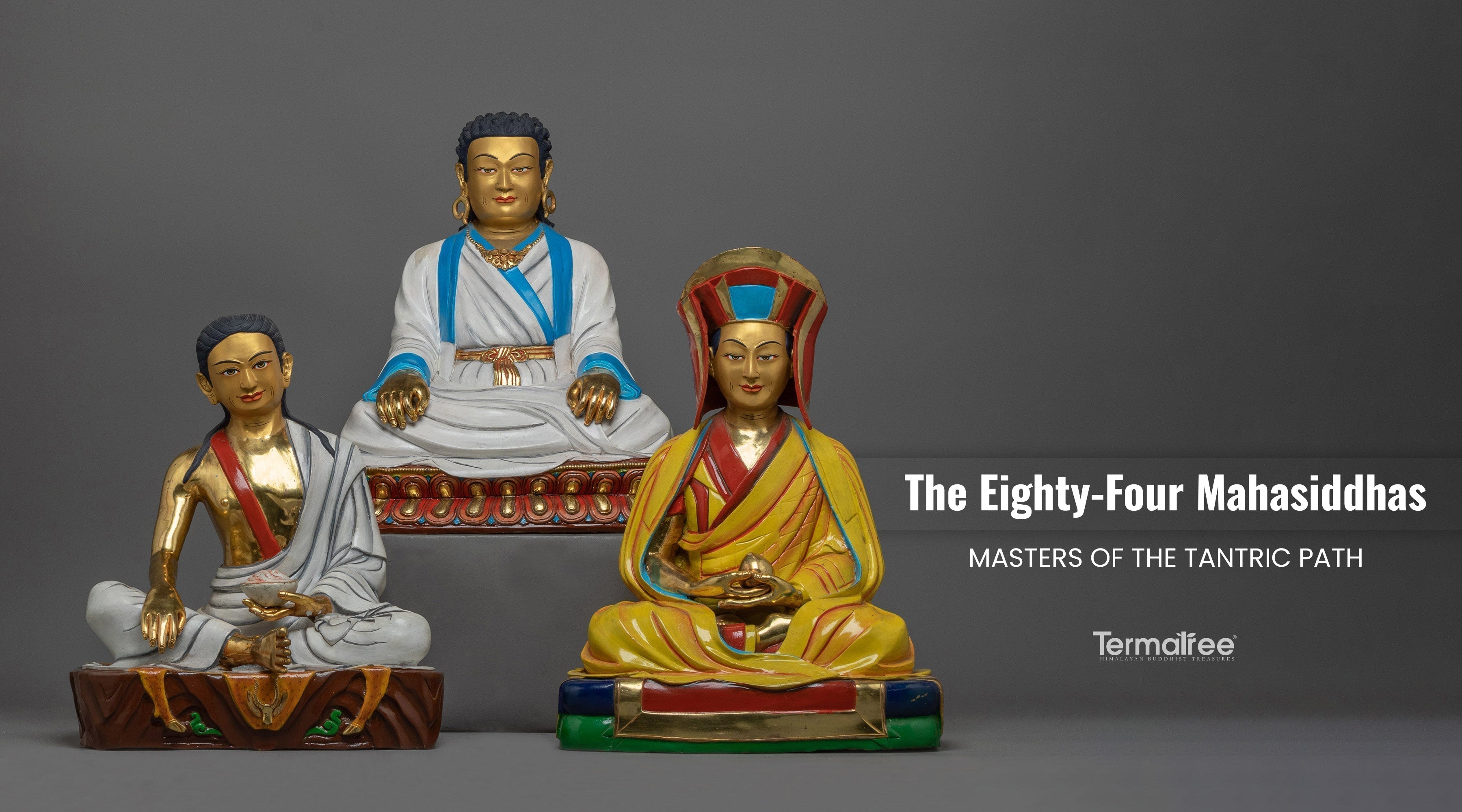

Mahasiddhas in Arts and Crafts

The influence of Mahasiddhas extend far beyond their spiritual and literary contributions, significantly shaping the development of Buddhist arts and crafts, especially within the Vajrayana tradition. Their unique teachings and unconventional life stories became the source of inspiration for a wide range of artistic expressions, including sculpture, painting, and ritual objects. This artistic heritage not only served to visually communicate the profound spiritual realizations of the Mahasiddhas but also reinforced key tantric concepts and practices central to Vajrayana Buddhism.

One of the most striking impacts of the Mahasiddhas on Buddhist art is seen in thangka paintings. The intricately detailed paintings on cloth, often depict the the great siddhas in their characteristic forms: engaged in yogic postures, surrounded by symbolic elements, or performing miraculous acts.

For instance, Guru Padmasambhava is typically depicted as a serene and powerful deity. His iconography often includes him sitting in a fully bloomed lotus throne. He may hold various attributes, such as a vajra (ritual thunderbolt), a bell, or a lotus. In addition to these, he is also surrounded by the Eight Auspicious Symbols of Buddhism, which are the conch, parasol, wheel, lotus, vase, golden fish, knot, and victory banner.

Meanwhile, thangkas of Tilopa often show him holding a fish or seated by the river, symbolizing his transformation of worldly activities into paths to enlightenment. Naropa is frequently portrayed undergoing his twelve trials, each scene illustrating a key moment in his spiritual journey. These visual depictions were not mere representations but served as meditative aids, allowing practitioners to reflect on the Mahasiddhas' teachings and integrate their wisdom into personal practice.

The artistic representation of the Mahasiddhas also introduced new iconographic elements in Vajrayana art. Their imagery often blended human and divine characteristics, reflecting their mastery over both the spiritual and material worlds. For example, Virupa is shown holding up his hand to stop the sun, a symbolic gesture that communicates his transcendence over time and space. These images were intended not only to evoke devotion but also to convey profound spiritual truths through symbolism. The depiction of their siddhis (miraculous powers) in these artworks was a reminder to practitioners of the extraordinary potential that lies within tantric practice.

Additionally, in these paintings the use of sculpture and ritual objects have been deeply influenced by the Mahasiddhas’ teachings. Statuary of the Mahasiddhas often portrayed them in dynamic postures, reflecting the intensity and spontaneity of their spiritual paths. On the other hand, the statues are crafted from precious metals such as bronze or copper and adorned with intricate detailing that are meant to serve both as objects of worship and as tools for visualization in tantric rituals.

Vajras, bells, and other ritual implements used in Vajrayana practice also carries symbolic meanings linked to the teachings of the Mahasiddhas. For example, the vajra is a symbol of indestructible truth and bell is a symbol of wisdom. They are central to Buddhism practices as a representation of the union of method and wisdom- core to their path of enlightenment.

Moreover, the Mahasiddhas’ influence also reached into the realm of mandala art. Mandalas are geometric designs representing the universe and are used as visual aids in meditation. Many of the siddhas are depicted at the center of these mandalas, surrounded by deities, consorts, and symbolic imagery, illustrating their role as spiritual guides within the tantric cosmology. These mandalas became essential in Vajrayana ritual practices, particularly in guru yoga, where practitioners visualize themselves as inseparable from their venerated guru. The intricate patterns and vibrant colors of these mandalas reflect the complexity and richness of the great teachers' teachings.

The crafting of ritual instruments and tantric objects, such as phurbas (ritual daggers), was also influenced by the Mahasiddhas. These instruments are not merely decorative but harbors deep spiritual significance. For example, the phurba was believed to have the power to destroy ignorance and obstacles, a concept that aligns with the Mahasiddhas’ transformative practices of turning ordinary experiences into paths of realization. Many Mahasiddhas, such as Guru Padmasambhava, are often depicted wielding these ritual objects, further cementing their association with tantric practice and empowerment.

The Legacy of the Mahasiddhas in Contemporary Practice

The eighty-four Mahasiddhas left an indelible mark on Buddhist arts and crafts. Their lives and teachings inspired a wide array of artistic expressions, from thangkas and sculptures to ritual objects and traditions. Their legacy not only celebrates their spiritual achievements but also serves as practical tools for practitioners. By incorporating profound symbolism and spiritual meaning into their depictions, these artworks perpetuated their teachings and has allowed their legacy to influence the future generations. This integration of art and spirituality in Vajrayana Buddhism continues to shape Buddhist culture and practice, making them central figures not only in the religious landscape but also in the artistic heritage of Buddhism.

The legacy of these great beings in contemporary Vajrayana Buddhism remains deeply influential, as their teachings, practices, and life stories continue to inspire modern practitioners across the world. Their impact on the Vajrayana tradition is multifaceted, encompassing spiritual methods, rituals, ethics, and the cultural transmission of tantric Buddhism.

The Mahasiddhas are seen as the embodiment of the tantric path, where both conventional and unconventional approaches to spiritual practice are honored. Their legacy shapes the way contemporary Vajrayana practitioners engage with their spiritual journey, particularly in terms of the rapid attainment of enlightenment, integration of everyday life with spiritual practice, and devotion to the guru-disciple relationship.

One of the most significant aspects of their legacy in Vajrayana is their emphasis on direct experience and non-dual realization. Modern Vajrayana practitioners still follow the core tantric methods introduced by the Mahasiddhas, such as mantra recitation, deity visualization, and yogic techniques like the "Six Yogas of Naropa," passed down through unbroken lineages.

These methods, which focus on transforming ordinary experiences into wisdom, are seen as potent means to achieve enlightenment in a single lifetime, a hallmark of the Mahasiddhas' teachings. This accessibility to enlightenment, regardless of one's social background or lifestyle, remains a central tenet of contemporary Buddhism practice, echoing their rejection of rigid societal and religious norms.

The guru-disciple relationship is a foundational element in Vajrayana Buddhism. It is deeply rooted in the tradition as those accomplished beings often exemplified the importance of devotion to a qualified guru for spiritual progress, as seen in the relationships between figures like Tilopa and Naropa, or Marpa and Milarepa. In modern Vajrayana, the guru is still viewed as the living embodiment of the Buddha’s wisdom, and the transmission of teachings through direct, personal guidance continues to be a central practice. This is particularly important in the context of guru yoga, a meditation practice where practitioners visualize themselves as inseparable from their guru, an approach that can be traced directly to the ancient teachings.

Another lasting influence of the Mahasiddhas is their integration of spirituality with everyday life, a principle that resonates strongly with contemporary practitioners. The siddhas had demonstrated that spiritual realization is not confined to monastic life since they lived as householders, ascetics, kings, or beggars, proving that enlightenment can be pursued in any context. In today’s world, where lay practitioners form a large portion of the Vajrayana community, this message is particularly powerful. It reinforces the idea that spiritual growth can happen amidst the complexities of daily life, as long as one’s intention and practice are sincere.

In addition to these spiritual practices, their ethical and philosophical contributions continue to shape contemporary Buddhism. The Buddhist masters' lives emphasized the importance of compassion and skillful means (upaya), showing that even the most unconventional actions, if rooted in wisdom and altruism, can lead to enlightenment. This flexibility in approaching ethical behavior resonates in modern Vajrayana, where the focus is on the intention behind actions rather than strict adherence to rules. The eighty-four siddhas demonstrated that breaking through conventional limitations, when done with insight into the nature of reality, can liberate both the self and others from suffering.

Finally, the artistic legacy of the Mahasiddhas, as seen in thangkas, sculptures, and ritual implements, continues to flourish in contemporary Buddhism communities. Their images serve as both objects of veneration and tools for meditation, in order to attain enlightenment.