Who Are the Citipatti?

In the esoteric world of Tibetan Buddhism, where life and death are experienced as one, few characters are more visually arresting and puzzling than the Citipatti—the dancing skeletal figures who frolic in the charnel grounds surrounded by flames and skulls. The iconography of the Citipatti is misunderstood to be a surefire invocation of death, when in actuality, they are warriors of impermanence, tantric protectors of sacred wisdom, and a reminder that the worldly and its attachments are transient. Their dance is not of death, but liberation through realization.

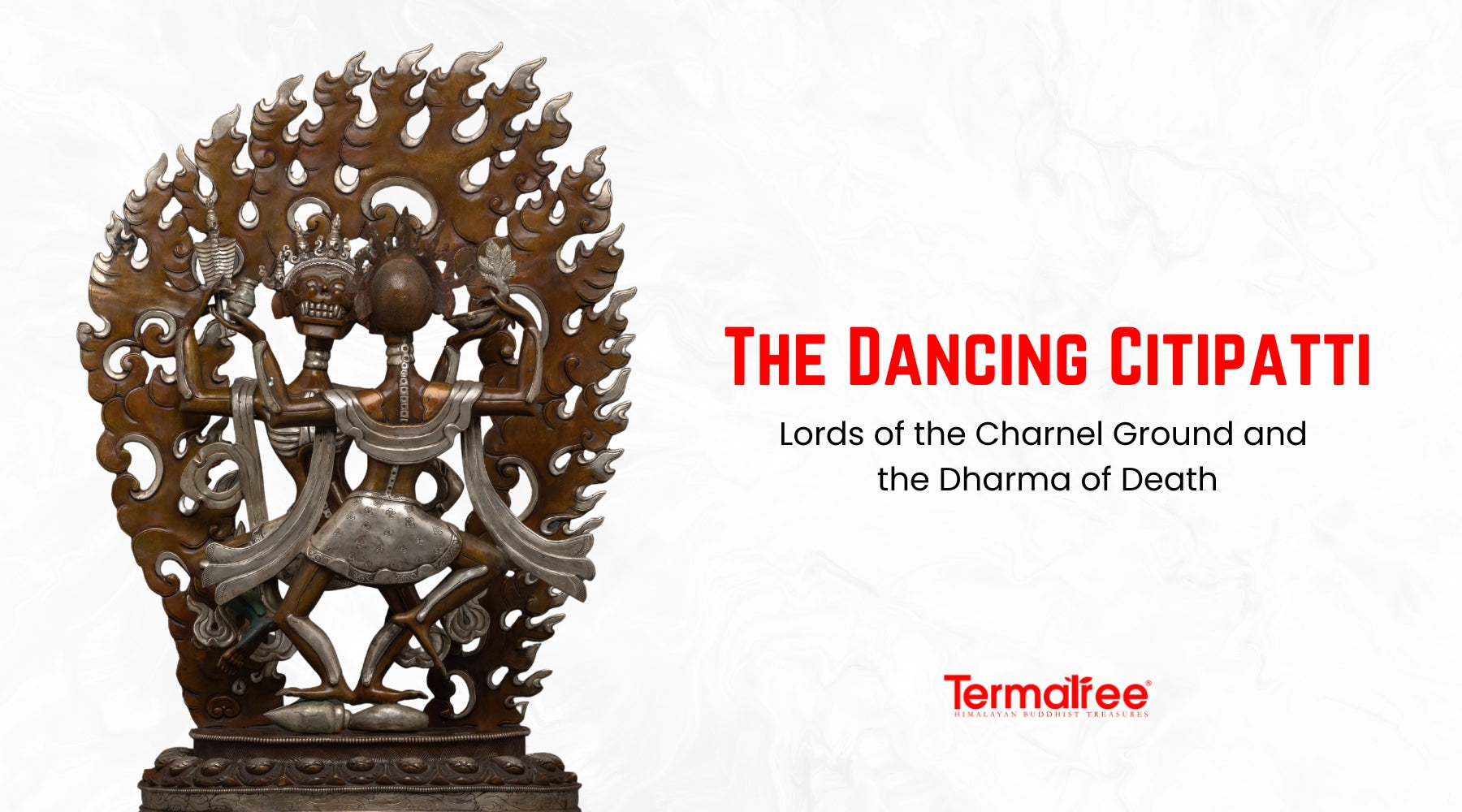

The Dancing Citipatti, which literally means "Lords of the Funeral Pyre" or "Lords of the Charnel Ground," are the most broadly recognized figures in Vajrayana imagery. Their grotesque skeletal appearance, often with a crown of skulls and garlands of bones, is not the precursor of morbid death but rather a visual mantra to direct practitioners on the path to enlightenment by embracing death as an important spiritual teacher.

In the following blog, we will examine their origins, symbols, iconography, rituals, and the dharmic meaning.

The Origin of Citipatti: From Monks to Lords of the Charnel Ground

A Myth Rooted in Renunciation and Meditation

In Tibetan legend, the Citipatti were once two very accomplished monks or yogis—a man and a woman—who were engaged in profound meditation in the wilderness. They became so engrossed in their meditation on shunyata (emptiness), on the nature of reality, that they failed to notice a bandit approaching who beheaded them in the charnel ground.

Their death, rather than disturbing the state in which they existed, became their last liberation. Their bodies died, but their minds transpired into the state of ultimate awareness. From then on, they became known as Citipatti—eternal skeletal guardians of Dharma, representing time and continuous meditation, the triumph over death.

Their transformation is key to their mythology; death is not the end, but rather a transition, while they serve as a reminder of this reality of spirit.

Dancing in the Flames: The Symbolism of Citipatti

Skeletons as Teachers of Impermanence

In almost all spiritual traditions, skeletons are associated with fear, decay, and the finality of death. In Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, however, skeletons like the Citipatti exemplify a teaching of the Dharma concerning impermanence, and explicitly point out that the body is impermanent and that attachment to it only brings suffering.

These lords depict death as starkly raw, and therefore force us to acknowledge anicca (the truth of impermanence) as one of the Three Marks of Existence in Buddhism.

Male and Female: The Union of Wisdom and Compassion

Citipatti are depicted as a male and female skeleton, often engaged in some fierce cosmic dance. Their limbs are intertwined, typically holding objects like a driguk (flaying knife) or a kapala (skull cup). This union is not simply a depiction of some kind of gender balance, but a proclamation of the inseparable union of wisdom (prajña) and method (upaya).

For Vajrayana teachings, duality needs to be transcended, and the sacred dance of the Citipatti provides a nice illustration that when death is seen clearly as a passageway, not a wall.

Garland of Skulls and Bone Ornaments

The bone ornaments of the Citipatti illustrate the six perfections (paramitas): generosity, morality, patience, diligence, concentration, and wisdom. The charnel ground remains that serve the Plumage signify that the Citipatti have abandoned worldly attachment and ego.

Their open mouths and ecstatic faces are laughing at the folly of permanence, dancing in bliss because they have transcended death.

Charnel Grounds: Sacred Spaces of Transformation

What Are Charnel Grounds?

Charnel grounds, or "durtro" in Tibetan, are open-air cremation sites that are dotted throughout the Buddhist regions of the Himalayas. These grounds are not just places to dispose of corpses in a sanitary fashion; they are fields of transformation, and in the context of Vajrayana, they are deeply sacred.

Monks, yogis, and advanced practitioners will go to a charnel ground to meditate on impermanence, even to enact tantrik rites in a shunned way in the company of ashes and bones. In Buddhist iconography, charnel grounds are commonly depicted at the periphery of mandalas or thangkas, as they symbolise the outer limit of ego-death, which is required before awakening. Moreover, charnel grounds are said to be the abode of wrathful deities and guardians, protecting the site so practitioners with sincere aspiration may transcend the illusions of this world.

Citipatti: Protectors of the Charnel Grounds

The Citipatti - two bony humans eternally dancing together - are popular and recognizable protectors of the charnel grounds. They may not elicit the same feeling of joy that the Buddha or bodhisattvas do, but they are not omens of bad things to come; instead, they represent liberated awareness. Their dance is a joyful recognition that their macabre form has no bearing on anything they do in the moment. They dance in and out of fires where corpses are burned, which helps communicate the Buddhist perspective that death is worth celebrating, not fearing, or avoiding.

Legend tells us that they were once powerful ascetics who used to meditate in a graveyard and were murdered by robbers. When they passed from this world, they came to a profound understanding and took on the role of protectors of the Dharma. In the present day, they are said to protect the charnel grounds, which means they ward off evil spirits, defilement, and obstacles to practice.

Additionally, the Citipatti embodies the simultaneous union of opposites, expressed as male and female, wisdom and method, life and death, etc. Their dance is a tantric celebration of non-duality, signifying the inseparability of form and emptiness. Their way of expressing joyful impermanence is to inspire practitioners to meditate and dance with death, instead of hiding by avoiding it.

Citipatti in Vajrayana Rituals and Art

Citipatti embodies the fearless wisdom derived from the experience of dying, encapsulated in the Vajrayana tradition. Although they are not major deities on the scale of Mahakala, they appear as part of ritual practices at a relatively advanced level, representing the severing of attachment and ego.

-

In Sakya, both figures hold a bone stick and a skull cup.

-

In Gelug, it is possible for the female consort to hold a sheaf of grain and a vase that represents fertility.

-

Within Nyingma’s Lama Gongdu, there are four skeleton couples, presented in color and vector style, and armed, where they do not have a concrete analogy or symbolism to Shri Shmashana Adhipati.

Additionally, they may appear in Chod rituals where practitioners visualize offering their body for the benefit of other beings and intentionally deepen their insight into emptiness, while not losing their human shape and things shaped into their minds.

Citipatti in Thangka and Sculpture

Citipatti uniquely appear in thangkas wherein they are dancing in flames amidst burial grounds and spirits. Sculptural representations of Citipatti typically show the main figures in yab yum, in an X or hs shape, while some may banally include slaughtered cadavers on paths, representing the death of ego, apart from something human.

Descriptions in the texts that compose ritual depict them as presented with shinning or luminous abstract colors, they could be described as intensely fierce, skeleton forms and for the sake of the catalog they would be holding a staff with a skull on the end, or a cup filled with said blood, and they are dancing through fire and surrounded by dakas.

The Dharma of Death: What the Citipatti Teach Us

Confronting Mortality as a Path to Enlightenment

For many, death is an unmanageable fear. The Citipatti teach that fear of death is ignorance, yet the more we fear death, the more we cling to our illusions. By meditating on death - imagining the lords- the practitioner learns to let go. Death eventually becomes a source of power: it strips the practitioner of illusion and propels honest spiritual practice.

The Five Dhyani Buddhas and Citipatti

Although the Citipatti are not directly related to the Five Dhyani Buddhas, they can play protective or symbolic roles in their mandalas, especially in wrathful mandalas. They may represent wrathful forms such as Heruka or Vajrakilaya, serving as guards or representations of transforming or liberating wrath. This connection shows that death also has a place in the mandala of enlightenment, not as an enemy, but as part of the journey.

A Mirror to Ego and Attachment

What takes place when one meditates upon the Citipatti? They see skeletons, but you don’t just see skeletons; you see your own decay, fear, and attachments staring back at you. In this sense, the Citipatti functions as a mirror, reflecting the futility of clinging to ego. In turn, they offer not despair, but freedom.

Citipatti and the Global Buddhist Audience

Rising Popularity in the West

Citipatti representations are quickly being embraced by contemporary practitioners in the West as fierce yet compassionate symbols of spiritual transformation through death. In a culture that often lacks conversations about dying, they serve as radical storytellers who confront impermanence. Their animated cadaverous forms connect purveyors of stripped-down texts in the pursuit of Buddhist knowledge, especially when considering the Vajrayana emphasis on death as a pathway rather than an end.

As a result, Citipatti icons have been embraced and increasingly adorn candle altars in an ever-growing variety of venues, including meditation rooms, yoga studios, and galleries. Statues of the dancing skeletons can be found well beyond temples. Their imagery appears in ritual tools, in elaborate thangka paintings, and even tattoos and other body art, especially among serious practitioners of Vajrayana who may holistically understand that these lords are not mere art, but living protectors of Dharma.

Surprisingly, the term "Citipati" has also entered the scientific community as the name of a genus of oviraptorid dinosaur – Citipati osmolskae. This dinosaur was discovered in the Gobi desert of Mongolia with its fossil remains in a brooding position over its nest. It was named after the Tibetan skeletal deities because it visually resembles a protector of death and rebirth. While it is not connected to Buddhist practice, the unexpected reference is interesting in the way the Citipatti figure reaches into the world of paleontology.

Misconceptions and Clarifications

Despite their recognizable appearance, the Citipatti are often misperceived (especially, outside of Tibetan Vajrayana contexts). Their skeletal form can lead to confusion with others’ wrathful figures, or sometimes demons, because of their appearance, especially given the skeletal remnants from caves. However, this perception is a misrepresentation that does not clarify the truth of their nature. These lords are not mischievous or malevolent. They are Dharma protectors representing enlightenment, utilizing a horrifying appearance out of compassion with the intention to disturb the mind's constructs about permanence, causing awakening to the truth of impermanence and liberation.

Also, it is important to understand that one should not confuse our deity pair—Father and Mother Citipatti— with the skeleton dancers who are part of, for example, a Tibetan Cham (ritual dance) performance. Even though both are skeletal, they occupy very different spaces. The skeleton dancers found in Cham are often presented as worldly spirits or as jesters, not as enlightened protectors. Generally, they can be grouped into three types, and they serve mainly to act as comic mascots or minor attendants to deities like Yama (the Lord of Death). They perform in narrative-related vignettes in ritual dances (for example, in the Black Hat Dance or Vajrakilaya Cham), and they rarely appear in thangka paintings except when the painting is depicting charnel grounds, in which case they are textually described.

In comparison, the Citipatti are not simply decoration or a narrative filler; they are sacred figures who are invoked in esoteric tantric practices. Their dance is not just a performance. It is a cosmic and sacred dance embodying the cosmological interplay between wisdom and compassion, between life and death. Although skeletons are a common representation of the wrathful deities and in charnel ground settings, only the lords of the charnel ground are personifying this sacramental union as fully embodied and awakened protectors and sustainers of the Dharma. It is imperative to understand this difference for the sake of understanding their role, but also not to collapse them into variations that detract from their profoundly important spiritual symbolism.

Closing Reflections: Why the Citipatti Matters Today

In today's context of death hiding behind hospital curtains and funeral home rites, the Citipatti are stark reminders of a declaration: death occurs. They do not favor avoiding death; instead, they move through it. Their skeletal forms dance expansively through cremation grounds barefoot on ashes and bones, indifferent to decay or fire. Their movement is raw and untamed, as they revisit the somber reality that bodies are not eternal, that life is momentary, and that grasping onto this life in fear or vanity will only create suffering.

But their movement reflects joy. The Citipatti do not mourn death; they rejoice in it. In this cosmic dance, their movement is liberation; their stance is kinship. Their dance involves opposites dissolving: male-female, wisdom-compassion, life-death. Their laughter resonates through the burning ground, not as insult but realization—impermanence is not a curse; impermanence is freedom. When we see them wrestling with death, we see that death can also be sacred, perhaps even more sacred, seen through the lens of Dharma.

Contemplating the Citipatti is to step into the fire. Not into a literal flame, but into the fire of fear, ego, and illusion. It's to sit with the truth of our mortality, not to turn it to despair, but to come to awakening. By facing what we most fear, we become naked, purified, and awakened to wisdom. Their dance calls us to live, not to find a way around death, but to live with the same clarity of being that fully experiences death. The Citipatti demonstrates for us not only how to die without fear but how to live without clinging.

2 comments

✏ + 1.36211 BTC.GET - https://yandex.com/poll/7HqNsFACc4dya6qN3zJ4f5?hs=2e929793bd595b6965424ee50f70afa4& ✏

e8ufih

📇 Notification; SENDING 1,247363 bitcoin. Continue > https://yandex.com/poll/7HqNsFACc4dya6qN3zJ4f5?hs=2e929793bd595b6965424ee50f70afa4& 📇

qgidqy