Aligning Body and Mind: The Wisdom Behind Vairochana’s Posture

The Seven-Point Posture of Vairochana is more than just a sitting position; it is a specific meditative structure that opens access to clarity of mind, balance of energy, and mental stillness. Posture in meditation is more than physical ease; it directly determines the quality of awareness and how subtle energetic currents move in the body. Of all the basic methods presented in Tibetan Buddhism, the Seven-Point Posture is the most ancient method and articulate alignment of body, breath, and mind.

The reference to Vairochana comes from the Vajrayana teachings and the concept of Vairochana as the primordial Buddha representing all-pervading wisdom — the clarity of the mind that reflects exactly the way things are. The seven points are not only mechanical or anatomical points of alignment, they are also psychological points of orientation that create the conditions to let the mind rest effortlessly in meditative absorption.

Even if the Seven-Point Posture of Vairochana was developed hundreds of years ago, it is still really relevant in the modern context. It provides practitioners with a stable ground in the swirling winds of life today and a subtle energetic architecture that nourishes awareness, insight into the spiritual dimension and a sense of genuine peace.

Why Posture is the Foundation of Meditation

In meditation, the body isn't merely a vehicle, but rather a participant in meditation. Its positioning can change how long you can practice, your quality of focus, and your energetic state overall. Generally, a slumped spine leads to dullness, and a tweaked body leads to restlessness. In contrast, a neutral spine will support wakefulness while providing comfort.

In Vajrayana and Mahayana texts, posture is often described as the "first step" to calm-abiding (śamatha). The body is situated so as to make it possible for the mind to rest without agitation and without fatigue. The Seven-Point Posture of Vairochana is an example of a neutral posture, since it is a neutral position that creates the conditions where the winds of the body (lung or prana) can flow freely and the mind can settle clearly.

What is the Seven-Point Posture?

The Seven-Point Posture is a meditative posture from Indian Buddhist texts, and was further developed in the Tibetan lineage. The Seven-Point Posture was taught by Indian masters such as Kamalashīla, and imbibed into Tibetan monastic training under figures such as Atiśa and Longchenpa. The Seven-Point Posture includes seven core physical alignments, all of which are both practical and symbolic.

Even as their physical forms may appear quite simple, there are deeper intentions behind them, and a deliberate intention to help facilitate the harmonization of the body's energetic channels to allow for stability while sitting in meditation. If practiced regularly, the Seven-Point Posture can produce a significant boost to concentration and clarity, both of which are essential aspects of meditation practice.

The Seven Points of Alignment

Let’s now explore each of the seven elements of the Vairochana posture and understand how they work together.

1. Legs Crossed in Vajra Posture

The first consideration is how you position your legs. The fully-lotus or vajra position, in which each foot rests on the opposite thigh with the soles facing up, is the ideal position. This posture is highly stable and symmetrical, which makes prolonged periods of sitting still easier.

That said, the full-lotus position is not accessible for everyone, particularly for beginners or those with limited mobility in their hips. As options, you can sit in half-lotus (with one foot resting on the opposite thigh), or simply cross-legged, with both feet resting on the cushion or on the ground. The main point is to find a position that feels grounded and will not require you to keep readjusting.

It is best to sit upon a firm meditation cushion (zafu) or a folded blanket, which will help raise the hips, tilt the pelvis forward, and align or stabilize and support the spine in a natural manner. If you cannot sit on the floor, you can also sit in a meditation bench or a straight-backed chair, as long as your feet are flat and your spine is upright.

2. Hands Resting in the Gesture of Meditation

Next, settle your hands into the Dhyana Mudra, or meditative absorption mudra. Place your right hand, palm up, over your left hand, palm up, with your thumbs touching, forming an oval or circle. This mudra is typically placed about four finger widths below your navel with your hands resting naturally on your lap.

In terms of significance, this hand position symbolizes the pairing of wisdom and method, two essential ideas in Mahayana Buddhism. In addition, this hand position fundamentally has a way of taking tension off the shoulders to help you find your center.

If the Dhyana Mudra doesn't feel comfortable for you at the moment, another option is to rest the hands on your knees; however, keeping the mudra for some length of time will take advantage of its energy balancing properties.

3. Spine Straight and Upright

You can think of your spine as standing up with strength and poise, like a stack of golden coins, or as a pillar of light. The alignment of your spine is the most important of the seven points! When the spine is straight, it encourages alertness and keeps the body's subtle channels of energy (tsa) open. When the spine is aligned, even the winds (lung or prana) can flow unencumbered through the central channel (avadhuti) and bring stillness to the mind. It is essential to try to avoid hunching/spinal slouching while at the same time overstretching or overly extending. Imagine there is a string gently drawing the crown of your head towards the ceiling. Keep the natural curves in the spine and allow buoyancy in your body.

This postural alignment leads to longer and deeper meditations and reduces the tendency for people to fall asleep or to have a dull mental fog.

4. Shoulders Drawn Back Slightly

Roll the shoulders back slightly and down, allowing the chest to open and create the experience of spaciousness. The aim is relaxed dignity, not stiff or slumping.

Besides allowing breath to flow more freely, an open chest subtly encourages the heart center to remain open. That physical openness reflects the internal spaciousness we are establishing in meditation.

Shoulder alignment also ensures there will be less physical tension building up in the upper back and neck, both of which can become distracting during prolonged sitting.

5. Head and Neck Balanced

Keep your neck straight and your chin slightly tucked down. This helps to elongate the back of the neck and brings the head in alignment with the spine as you are looking down as a natural way to help with an inward meditative focus. Avoid tilting the head back and do not let it droop forward. Imagine the crown of your head gently gliding up and up as your chin follows in a line with the spine. The head should rest comfortably without strain.

The position supports mental alertness while safeguarding you from becoming mentally dull or drifting into sleep.

6. Tongue Touching the Roof of the Mouth

Lightly rest the tip of your tongue against your upper palate, just behind your front teeth. This is a subtle yet powerful part of the posture.

Doing this will help keep the saliva flowing, so you don't have to keep swallowing all the time. This creates a small energetic seal to help circulate some subtle winds in your body. At first, this may feel awkward, but most practitioners find that it becomes second nature with practice. Let your jaw be relaxed, with your lips very slightly parted, or perhaps closed without tightening.

7. Eyes Gently Open and Relaxed

To conclude, it is recommended to keep your eyes half-open with your gaze down the line of your nose or toward a point on the floor a few feet ahead of you. The gaze is soft, not focused, just open and relaxed. This will help to avoid drowsiness (which often occurs with closed eyes) and lessen visual distraction. The experience will be more about presence and non-duality, the joining of inner and outer awareness.

If keeping your eyes open is too distracting in the beginning, then you can start with your eyes closed. However, as you go along, learning to meditate with open, or half-open eyes is something to aspire to.

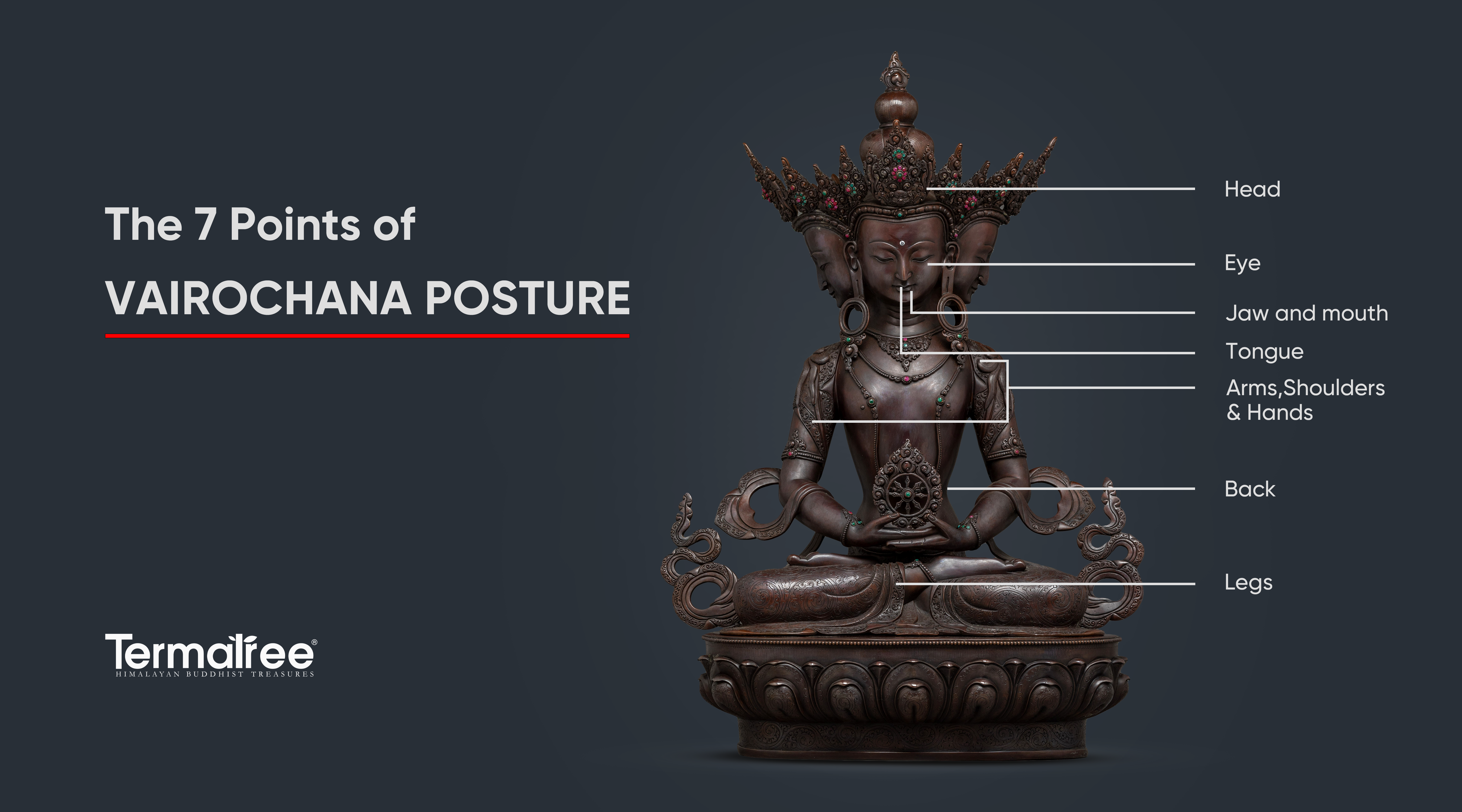

The Seven-Point Posture in Himalayan Buddhist Art

In Himalayan Buddhist art, whether in sculpture, thangkas, or murals, the Seven-Point Posture of Vairochana is a subject that is often rendered with great care. These images do not simply provide a representation of a figure in seated meditation; they encapsulate a set of codified visual forms of inner tranquility and yoga mastery.

Whether cast in bronze, painted on silk, or carved into temple walls, sculptures of Buddhas or great meditation masters will often be rendered according to iconographic conventions in order to demarcate the seven points of the Seven Point Posture: legs crossed in lotus, Dhyana Mudra, upright spine, relaxed shoulders, chin slightly down, tongue resting, and gently focused gaze. The result will be a depiction of perfect symmetry and calm presence.

These representations are not simply aesthetic concerns. Rather, they are educational devices---allowing practitioners to visualize desirable qualities associated with an idealized posture. The calm gaze, stable seat, and upright spine portrayed in these images can be didactic cues for how to sit, breathe, and be. Ancient artists were not simply artisans but were also enabled through their craft as spiritual practitioners who recognized that the external form is a reflection of their inner state.

By meditating on the artworks, or simply looking at their shape, practitioners can learn the values of the Seven-Point Posture through visual resonance. In this way, art reflects meditation itself, directing the practitioner’s body, energy, and mind toward the exact alignment.

Benefits of Practicing the Vairochana Posture

Physical Stability

With a solid foundation and upright spine, this posture enables you to stay seated for a long time without pain or discomfort. It promotes natural stillness, or less shifting, or less fidgeting.

Mental Clarity

The posture also promotes balanced awareness. It balances alertness with relaxation, which is essential for developing the kind of concentration (samadhi) necessary for deep meditation. Many practitioners relate their capacity for deep focus reaches a new depth when the body is correctly aligned.

Energetic Flow

When the spine, breath, and subtle body channels are aligned, the movement or the flow of the inner winds, or prana, is unrestricted. Tibetan texts are very clear about the significance of prana for advanced meditation practice—indeed, the potential for the recognition of subtle experience, such as clear light mind.

Symbolic Power

Every point in the posture has a symbolic meaning. For instance, the lotus position represents unshakable commitment, the mudra indicates the unity of wisdom and method, the straight spine evokes moral integrity, etc. So, sitting in this posture is not only an intrinsic part of the meditative path, but it has also become a ritualized expression of that path.

Adapting the Posture for Your Body

It is worth noting that although the complete Vairochana posture is the gold standard, it is not necessary to begin in the whole posture. If you have any physical conditions, feel free to adapt it. You could use a chair, pads, stretch before you sit, take breaks, etc. What matters is the spirit of the posture—intentional, stable, aware.

Even experienced practitioners may get sore, especially in the early stages. That's alright. The body is learning. What is important is consistency and intention.

Practical Tips for Beginners

-

Use a firm cushion or folded blanket to elevate your hips.

-

Start sitting in short sessions (5–10 minutes); gradually increase the amount of time.

-

At the beginning of your session, always check your posture with a quick mental body scan.

-

Stretch gently before sitting—especially the hips, knees, and back.

-

Do not force yourself through pain. Modify your posture to your comfort level, then return to stillness.

-

Use a meditation timer with soft bells, so you can focus on your practice instead of glancing at a clock.

Integrating the Posture into Daily Practice

A monastery or a perfect meditation hall is not needed to practice this. The Seven-Point Posture can be done in your bedroom, a corner of your house, a nice spot in nature, or even a seat at your office, when you take a breath. The best part is that it can be done anywhere, and a few breaths, with focused awareness, will convert any seat into a seat of stillness. Just begin.

The only requirement is to sit with intention and establish one point at a time, gently and without judgment. It will take your body to learn the form, and for your awareness to be still. The posture will slowly go from technique into second nature, and with time, more than the excuse for meditation, it will be a calm threshold of your daily presence, which holds both formal practice and the unknowable trajectory of your spiritual life.

Final Thoughts: The Posture Becomes the Practice

At first, the Seven-Point Posture can feel like one more thing to "get right," like a checklist of adjustments to your physical form. As you practice with patience, however, it becomes an abiding container of presence, a living expression of discipline, devotion, and inner spaciousness. In stillness, you will find your mind has space to breathe and awareness has space to shine.

The Buddha taught not only meditation but also how to embody meditation. And by taking this posture, representing the cosmic Buddha Vairochana, we are not just sitting; we are using a posture that connects us to a lineage of wisdom that has shaped countless minds and awakened countless hearts.

So find your cushion, settle your body, align the seven sacred points, and begin.

Your path to stillness, insight, and awakening starts with a single deep, well-balanced breath.

1 comment

📉 + 1.793717 BTC.GET - https://graph.org/Payout-from-Blockchaincom-06-26?hs=656ff3e0efe26c5f5c1d2b5565335890& 📉

o13vqj